What International Brands need to know about Indian Consumers: To sell in India is to deeply understand it's Colonised Legacy

A socio-cultural lens on history of India for the modern business.

There is a word I love - Sankofa (SAHN-koh-fah), Twi word from the Akan Tribe of Ghana that loosely translates to, “go back and get it.” meaning to go forward, you need to understand the past.

The brouhaha around this month’s Met Gala, particularly the backlash over Cartier declining Diljit Dosanjh's request to wear the original Patiala Necklace - a 1000-carat diamond piece created by Cartier in 1928 for the Maharaja of Patiala, alongside TikTok’s never-ending reels rebranding a humble Indian dupatta as “Scandinavian,” speaks volumes.

These conversations point to something simple but deeply felt: Indians want to be seen, and seen right, on the global stage. With respect and authenticity.

Every time I go back home to New Delhi, I feel like I’m standing in the nucleus of the world. You can sense the pulse of the city - the spirit of commerce in the air, the friction of a society evolving at high speed, and an underlying rhythm of jugaad woven into everyday life.

Alongside this, there is a sense of deep self-affirmation. The modern Indian consumer is not passive aspirer waiting to be told what’s cool. They know their history and they expect brands to keep up - not catch up.

Yet, despite this massive appetite for growth, dynamism and stories worth telling, international brands have historically approached India with a mix of exotification, definitely curiosity, but a lot of caution - often stopping short of real inclusion.

Some exceptions exist: real moments in pop culture like the haldi ceremony scene in Bridgerton, a nod that felt nuanced and celebratory, not performative. Just yesterday, Alia Bhatt’s red-carpet appearance at Cannes in a Gucci saree-lehenga hybrid, embellished with the brand’s signature monogram, received a moderately positive response from Indian influencers and media - a huge feat in itself.

I’ll take a hard line on design first: if you're an international brand designing for India, Indians should be leading that vision. Ideally, someone who’s grown up in the country, who understands the culture not as an aesthetic but as a lived experience. And if that’s not possible, at the very least, work in close consultation with those who do. If you're a foreigner designing for India, the bare minimum is this: go to India.

To sell in India, you need to understand India. To understand it is to love it and loving India takes time. Trust is earned through understanding - and there are no shortcuts.

This essay aims to begin that exploration - through history of current consumers, through stories of their parents, through data, and through the lens of a country that is shaping the future of global fashion and luxury in seismic ways.

This is the time to really understand it.

Part I: The Post-Colonial Consumerism and the Many Indias Around the World

I remember growing up in the '90s India as being a special time. The economy had just liberalised, opening its doors to foreign brands, and the first generation born after independence was now in its 30s and 40s, the Gen X steering the rise of a vast, ambitious middle class. It meant possibility - a collective national shift from scarcity to aspiration.

Despite this growth, partition memories, the collective wound of displacement lingered in homes across the country.

This was also the era of peak brain drain - when the brightest minds left for opportunities abroad. Yet, even as many physically left, their connection to India remained deeply emotional. Spice boxes were sent across oceans - culture travelled in suitcases and a new generation of the Indian diaspora was born. With the diaspora also came the deep desire to hold on to identity, sometimes in the most stereotypical ways.

There are many Indias around the world today.1

In Vogue Business, Yash Dongre, the Head of Business for Anita Dongre, who has opened brand stores in New York and Dubai said: “We would have brides and grooms fly into the Mumbai and Delhi stores from abroad and even return with family members and friends for their weddings. It is this strong overseas demand that prompted us to open a store in New York. The store did much better than our initial expectations. The Indian diaspora globally has grown over decades and across shifting geographies, but what remains true across generations is the idea of culture and purpose.”. When it comes to occasions such as weddings, or celebrations like Diwali, Indians, whether they live in India or abroad, still turn to homegrown fashion. 2

With the tapestry of the indian diaspora’s connection to home evolving with the times, it’s crucial to get what the times are.

Let’s look at the complexities of these Indias.

India’s Consumption Story | A journey through the post-independence decades

1950s: Suspicion, Nationalism, and Self-Reliance

Key drivers of consumption | Fresh in to the decade post-independence, the core feeling amongst Indians is pride in self-sufficiency, Gandhi’s Swadeshi (meaning: of one’s own country) movement was very relevant to a free India’s desire towards consumption.

What people were buying | Hand-spun khadi symbolised nationalism. Masses of handwoven fabric were woven for simplicity, self-reliance and equality in the backdrop of Nehruvian Socialism. Masses wore handwoven due to affordability

Perception of foreign goods | Elitist, Immoral

What consumer class consisted of :

Elite Anglicised, exposed to imported luxuries (albeit scarce).

Middle class: Small but emerging, state-employed.

Masses: Agrarian and subsistence consumers.

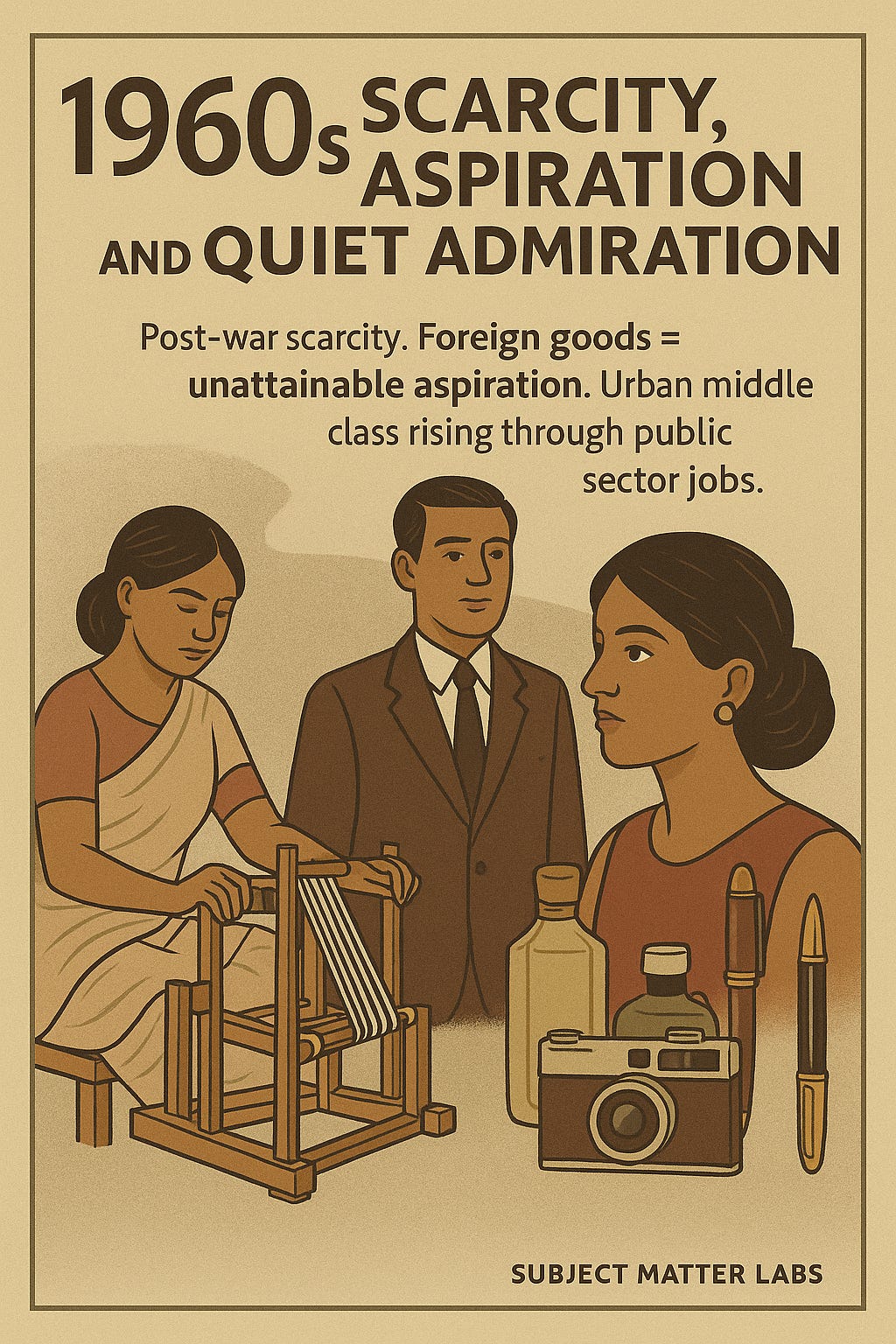

1960s: Scarcity, Aspiration, and Quiet Admiration

Key drivers of consumption | India fought two wars in this decade, so it was marred by scarcity and recovery. Industrial production was still catching up and while state planning dictated essentialy, some level of quiet fascination with foreign good began to grow.

What people were buying | The majority of fashion was handmade, however, urban consumers started moving towards mill-made for convenience.

Perception of foreign goods | Unattainable aspiration. Items like foreign soap, perfumes, pens, or cameras seen as status symbols. Existing elite and diplomats had limited access and therefore, heightened mystique.

What consumer class consisted of :

Urban middle class slowly started rising through public sector jobs.

Rural market, not yet consumer-driven.

1970s : Contradiction: Socialist Outwardly, Covetous Inwardly

Key driving of consumption | Emergency, inflation and tightened import restrictions are the core drivers of this decade. Consumption was driven by Black markets and smuggling of goods within the country.

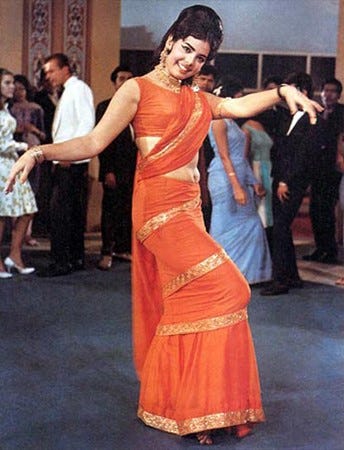

What people were buying | Regional crafts like Chanderi, Kanjeevaram gained spotlight through Bollywood movies and state emporiums were set up. Some describe this era as “socialist chic”, since khadi was primarily worn by the leftist factions of the society. Gifting foreign products (e.g., perfumes, chocolates, Walkmans) was a sign of elite generosity or NRI connection.

Perception of foreign goods| Public disdain but private desire. Politicians and bureaucrats discouraged foreign goods - yet many used them discreetly. Some foreign goods had cult status, specially Japanese electronics, Swiss watches, or Scotch whisky.

What consumer class consisted of | Only the upper class had access to foreign goods via diplomatic or business channels, even though the desire proliferated all class, especially as Bollywood glamorised imported items: watches, perfumes, gadgets.

1980s Aspirational Globalism Under Wraps

Key drivers of consumption | This decade marked the rise of the Indian consumer brands and the middle class. Expansion of public-sector and white collar jobs through liberalisation of technology imports was visible.

What people were buying | Homegrown brands, like, Bajaj scooters, Hero cycles, Onida TVs, Goldspot/Thums Up soft drinks. There was an increased curiousity for western brands from young consumers who began idolising western fashion and music like Michael Jackson or Madonna, to name a few. “Imported” became a keyword in ads, even for fake or local goods.

Perception of foreign goods | Cool, Desirable, Out of Reach.

Brands like Sony, Panasonic, Levi’s, and Bata (often mistaken for foreign) had cult status and several Indian knock-offs of foreign brand proliferated the market.

What consumer class consisted of | The key highlight of this decade was women emerging as consumer, leading with cosmetics and kitchen appliances as key categories. Middle class expanded given the better access to education and salaried jobs.

1990s Open Embrace of the Global Consumer Dream

Key driving of consumption | In 1991, the government of India introduced a series of reforms to encourage private-sector paticipation in the economy, attracting foreign investment, increasing ease of doing business and stimulating various sectors of the economy. Cable TV was one conusmer product that brought in global advertising and imagery.

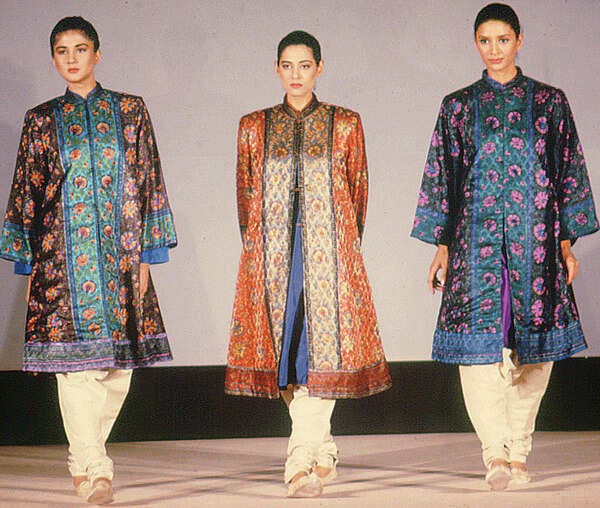

What people were buying |Brands became markers of upward mobility. Khadi was viewed as outdated or rural by youth, yet handloom retained prestige in elite and ceremonial circles. FabIndia gained traction among expats and urban liberals, ethnic day in offices became common. India’s early luxury interest in handloom began, visibly through Ritu Kumar, Sabyasachi’s early work, for example.

Coca-Cola, Levi’s, Maggi noodles, Maruti cars, mobile phones (late 1990s).

Shift from durable goods to lifestyle: cosmetics, packaged foods, branded clothing.

Perception of foreign goods | Modern, Aspirational, Normal.

Global brands brought in Western packaging, aesthetics, advertising, altering taste and brand expectations, hence owning a foreign brand became a middle-class dream.

What consumer class consisted of | Indian youth especially led the charge in adopting foreign brand culture. The urban middle class exploded in size and influence, led by Tier-1 cities which were consumption hubs.

2000s Global is Good, But Local Can Compete

Key driving of consumption | The IT boom created global exposure and increased spending power. The presence of malls, retail chains, and multinational brands saw globalisation of culture. Credit cards and EMI culture on the rise.

What people were buying | Branded apparel (Nike, Adidas), cars (Hyundai, Honda), mobile phones (Nokia) grew as categories. Fast food chains (McDonald's, Domino’s), multiplexes grew rapidly across urban and sub-urban. Bollywood films would showcase Indians abroad with many plot lines based on diaspora living across US or Europe.

Perception of foreign goods | Trusted and Desirable, but increasingly normalised. The elite began differentiating via niche foreign brands. Emergence of local Indian brands competing on style and quality.

What consumer class consisted of |

No stigma or guilt in consuming foreign products.

Mass affluent and new middle class emerged.

Tier-2 and 3 towns start consuming aspirational goods.

2010s Hybrid Tastes, Digital Globalisation

Key drivers of consumption | The rise of e-commerce and influencer culture - consumption is driven through Amazon, Instagram and Youtube influence.

Smartphone + mobile internet revolution (Jio launch in 2016).

E-commerce boom: Flipkart, Amazon, Myntra.

Demonetisation (2016), GST rollout (2017).

What people were buying | The era of fast-fashion (Zara, H&M), online shopping and smartphone-led brand discovery. Experience economy thrives through travel, dining, streaming, fitness.

Perception of foreign goods | Foreign = Lifestyle alignment, not just aspiration. Foreign products are judged on value, innovation, and aesthetic, not origin, for eg. Korean skincare.

What consumer class consisted of |

Digital-native Gen Z and millennials drove trends.

Rural consumption picked up via mobile connectivity and subsidies.

Rise of influencers and social commerce.

2020s (so far) Cultural Sovereignty Meets Global Taste

Key drivers of consumption | The pandemic shifted focus to local resilience, craft revival and increased the tempo on climate consciousness and sustainability awareness. “Vocal for Local” renewed the focus on craftspeople. While Gen Z and millennials more conscious of ethical sourcing, the infrastructure has also change with rapid fintech adoption (UPI, BNPL).

What people are buying | D2C brands (Mamaearth, Boat, Raw Mango, Forest Essentials, WOW), Tech-enabled services (OTT, edtech, grocery), EVs, organic foods, athleisure wear.

Perception of foreign goods | Optional. Foreign doesn’t mean better - cultural storytelling and brand values matter. Luxury brands perception comes from product quality, not just foreignness.

What consumer class consists of |

Digital-first, mobile wallet user with a blend of aspiration and awareness.

Bharat v/s India divide is narrowing in terms of consumption: Tier-2/3 cities are emerging hotspots of growth.

Women and Gen Z are powerful consumption drivers.

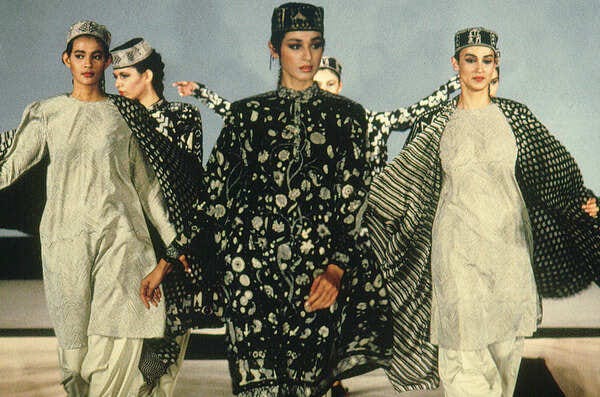

Part 2: Handmade to Haute: The Convergence of Craft and Luxury in India

In India, handmade and luxury once sat on opposite ends of the cultural spectrum. Handmade textiles, especially khadi, were born of freedom struggle, still reminiscent of it. [So when Viviene Westwood in 2025 decided to do a capsule collection in Khadi, was a reminder of self-reliance and nationalist pride. To do justice to this collection was primordial]. Luxury, in contrast, was tainted by colonial excess, a symbol of zamindari wealth and western clubs. But over the decades, as India evolved, so too did the meaning of both.

Handloom continued to be a form of political expression. Meanwhile luxury became performance - reflected in weddings, film stars, and imported rituals.

By the 1990s, as liberalisation cracked the market wide open and global brands arrived. Handmade struggled for relevance but found new life through niche revivalists. State emporiums and street markets in cities, such as Dilli Haat in New Delhi, were purveyors of handmade, giving direct market access to artisans.

Then came the 2000s. FabIndia, Good Earth, and boutique brands redefined handmade as chic, conscious, and curated. Craft became urban.

As for luxury, the wedding industry exploded into a theater of soft luxury - rituals dressed in designer threads. The trend of big Bollywood wedding theatre seeped into the culture with luxury being defined as designer trousseau, destinations and curated sets and professional programming.

Now, in the 2020s, Gen Z is merging the worlds of craft and capital. This shift is still emerging, especially given the price sensitivity of a large portion of Indian consumers. However, the cultural conversation is evolving fast. Handmade is no longer seen as old-fashioned, it's a form of activism.

The knowledge of weaves, prints and Geographical Indicators is considered relevant and important, moving away from virtue signaling to actual interest and nuanced knowledge. This cultural movement is driven by metropolitans cities, to be honest.

That said, many Indian consumers still associate luxury with global fashion houses rather than indigenous craft and therefore, Indianisation is no longer optional, it’s essential.

Part 3: The Future: Gen Z, demanding not perfection, but acknowledgement

With over 400 million GenZ consumers in India, this demographic holds significant sway over the country’s consumer landscape. According to Nielson3, “High sense of collective identity” is one of the key markers of this section’s consumption patterns. “GenZ takes pride in the growth story of India and wants to participate in it, which has led them to embrace values of diversity, agility, rootedness and authenticity.”

Gen Z accounts for 46% of global consumption, with spending power projected to reach $12 trillion by 2030.

Gen Z shopping preferences are heavily driven by culturally immersive experiences - storytelling, symbolism, and sourcing of the products. 4

Gen Z in India doesn’t want you to be perfect, it wants acknowledgement of culturally rooted influences.

Not everything’s perfect: Indian Luxury Market has Miles to Go

India’s growth story is, of course, not perfect. India is not going to be the next China in luxury consumption, by miles.

The target customer segments in India are smaller in comparison and have lower incomes compared to their global counterparts. This can be attributed mainly to the country’s wealth distribution profile. Around 75 percent of Indians have a total wealth of less than $10,000, with only 2 percent exceeding $100,000.

India’s inconsistent infrastructure and fragmented regulatory environment, split between state and central laws, make market entry complex for foreign brands. Luxury labels often face hurdles around logistics and compliance. Many are required to form joint ventures with local partners, adding another layer of complexity.

Having said that, Indian luxury market is fastest growing in Asia and second fastest in the workd - it is the perfect time to enter and operate in India. For luxury companies, it might take awhile to understand and adapt to this market, due to its complexities and pluralities of many Indias.

The government has launched a variety of initiatives to increase India’s attractiveness to foreign investors and increase internet coverage. If these pay off, they could lead to an increased luxury presence in India.5

In the landscape of India’s already thriving handmade market, the need of the hour is to modernise without altering, and represent without appropriating, keeping artisanship and its diverse craft cultures at the core.

India’s past stands as a testament to the nation’s deep-rooted nationalism and enduring appetite for craft. While the growing allure of global fashion is undeniable, the market remains anchored in a rich cultural and political heritage, layered with pride and resilience, even as it looks outward to internationalise on its own terms.

The real key to navigating this market lies in understanding where it coming from.

Vogue Business: How luxury brands can tap into Indian diaspora