SHEIN Arrives in France: A Brand Strategy Blunder or A Paradox Between Cultural Ideals and Economic Reality?

SHEIN’s entry into France showcases paradox between consumer sentiments and consumer behaviour

Reading time: 6 minutes

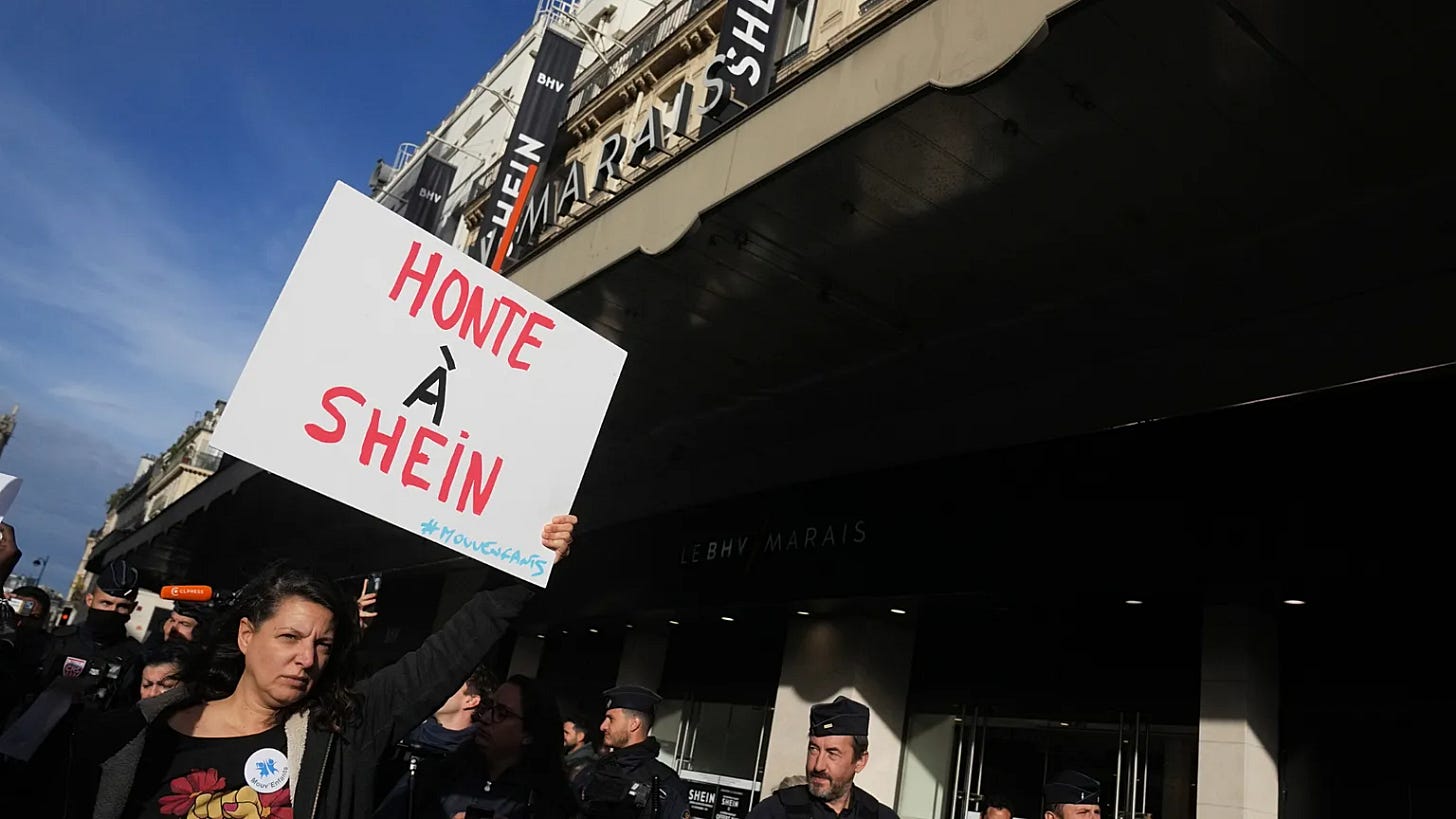

Paris just rolled out the red carpet for SHEIN, with a brick-and-mortar store, none other than the iconic BHV, stirring up drama that’s got government, activists, and fashion industry squirming. I must admit that this is physically painful, so let’s call it what it is: the world’s most infamous (ultra) fast-fashion brand cozying up to one of the biggest fashion capitals in the world in a attempt to clean its image.

Stealth Mode Tactic

Not only was it an odd pairing, but it was also done so quietly that no one noticed. Not a peep about SHEIN x BHV until just before the opening day. It might come as a shock to you but many stakeholders, non-profits, journalists and such, did not realise it was supposed to be SHEIN’s first permanent flagship store in the world, many thought this would be a pop-up.

The press release came out only about a week before November 5, 2025, the launch day.

The outcome was revolting for some consumers and shocking for activists and media alike.

Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo’s office later admitted that Hôtel de Ville (or City Hall) wasn’t informed that SHEIN would be occupying space in BHV.

(By law, BHV did not need to get approval from the city for a concesSo, city officials only responded after the store was publicly open.)

That was the beginning of the catastrophe: the brand tainting of BHV, and the actual exodus of brands from the mall.

Herein lies the dichotomy. Not only has this fast-fashion brand tried to find a fit in one of the fashion capitals of the world, a culture that respects savoir faire, but has also targeted some of the iconic retail locations for it, namely, BHV or Bazar de l’Hôtel de Ville, a place for French-made prêt-à-porter.

You might think: how does a brand like SHEIN think this country and this location is a fit for a physical store, and how does it hope to succeed here?

In many ways, this is a classic story, one that reveals much about human values and desire. We’re going to dive deep into all of it today.

Part I. Why Start With France and Why Now?

“By choosing France as the place to trial physical retail, we are honoring its position as a key fashion capital and embracing its spirit of creativity and excellence,” said Donald Tang, SHEIN’s Executive Chairman.

SHEIN’s intent for France was : let’s try the hardest market first.

They have the following rationale:

From the revenue standpoint:

France represents roughly 5–6% of global sales, making it a top 5 markets, up there with US, followed by Germany and UK.

Amidst the biggest fast fashion players in the French market, such as, Zara (Inditex), H&M, Kiabi, Jennyfer, Temu (online imports), SHEIN is a major disruptor in France. It has been able to dominate these markets through aggressive digital marketing, ultra-fast logistics, and adaptation to local market preferences, particularly among Gen Z shoppers.

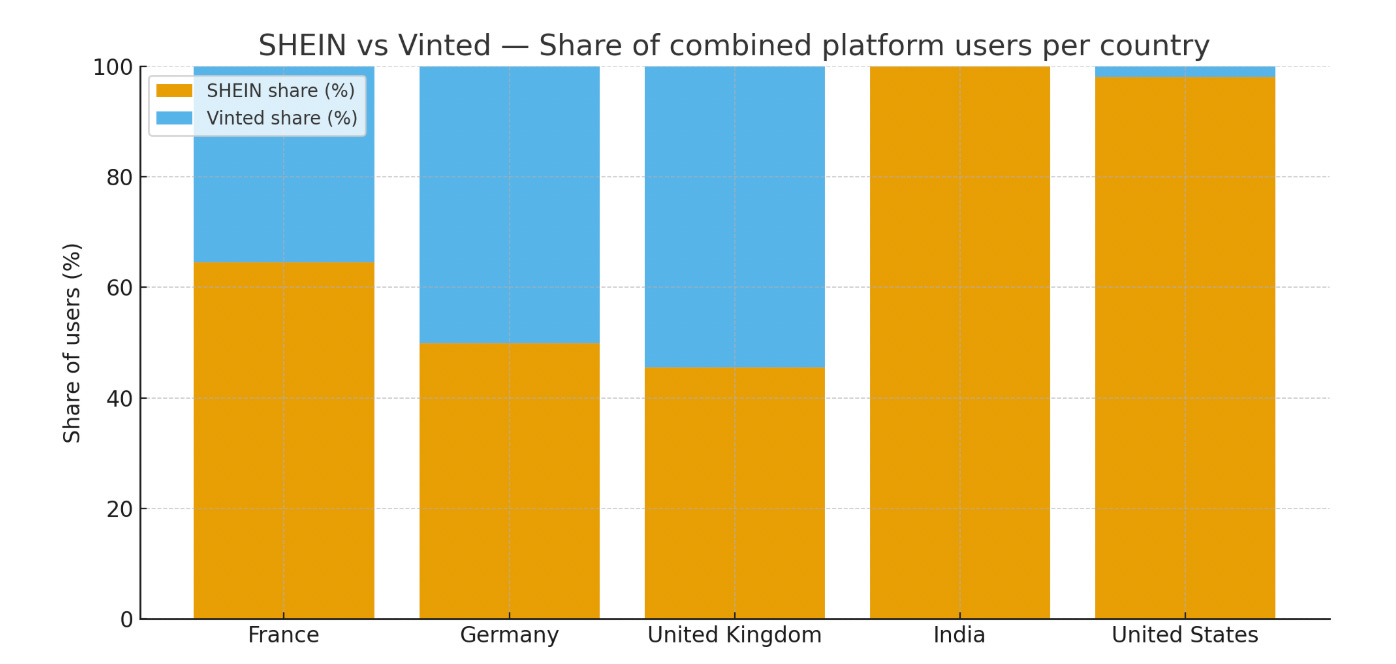

While Vinted is the biggest ecommerce player in the French market, by % share of users in France, SHEIN takes the bigger pie.

From regulatory standpoint:

France has some of the strictest sustainability and consumer-protection laws in the EU, SHEIN reportedly saw value in adapting to France first to later claim EU-wide compliance leadership.

This also ties into their ongoing plan to IPO in 2026, for which European ESG compliance is crucial.

Their brand strategy was built on the following hypothesis:

Legitimisation & brand prestige

By opening a store in Paris, one of the world’s fashion capitals, SHEIN was clearly trying to make a point. They were also trying to experiment.

The Brand team within SHEIN imagined that this move would position them alongside luxury names (BHV and Galeries Lafayette are historic institutions), a way to rebrand from “cheap e-commerce” to “accessible fashion with experience.”Consumer trust & sensory validation

As per a study by Ipsos, French public lists price (62%) and quality (58%) as the top criteria when buying clothes; values like sustainability come lower (32%). Having said that, through the same study, we can see that 52% of people are opposed to SHEIN opening a store in the iconic department store BHV Marais in Paris.Despite these studies, SHEIN reflected that seeing, touching, and trying items before ordering online would increase credibility and reduce return rates in the future.

Local expansion pilot

Paris was meant to be the test case for a broader French rollout: five more cities were planned (Dijon, Reims, Limoges, Angers, Grenoble) via similar department store corners.

Part II. What does this say about the consumer market in France? A cultural and economic paradox.

Five years in Paris taught me one thing: French consumers give a fair amount of damn about sustainability and knowing where their clothes come from. Fashion here thrives in originality, hunting for beauty in high and low, vintage gems, keeping your old pieces alive, repairing instead of tossing, and cheering on small makers.

Call it confirmation bias, and a little bit of romanticising, if you like but, many French consumers and industry voices see SHEIN’s ultra-fast-fashion model as contrary to French fashion culture, which emphasises quality, durability, craftsmanship.

But people only put their money where the mouth is when things are alright. The economic reality of most French consumers does not necessarily overlap with its cultural ideals of eco-fashion and preserving heritage and savoir-faire.

French consumers, especially under 35, face stagnant wages and high living costs (housing, food, transport).

INSEE data (2024) shows the average disposable income per capita grew only ~1.2% after inflation, far below the EU average.

The result is that people want to buy ethically, but can’t afford to at scale.

Eco Anxiety + Convenience Paradox

Surveys show that while nearly half of French consumers report negative views of SHEIN, a striking 43% of 18–34-year-olds admit to buying from the platform recently, often justifying these choices as occasional or “just for specific trends”.

This compartmentalisation, or moral rationalisation, reflects a broader global tension when talk about sustainability: people espouse green values but face real financial or social pressures that steer them toward convenience and cost-saving options, creating what some call the “eco-anxiety + convenience paradox”.

In practice, economic realities and peer influence can outweigh sustainability ideals, leading many to accept compromise purchases as minor or necessary.

Dr. Guillard, a leading researcher in consumer behaviour, explores the forces driving today’s fashion consumption. Her work reveals how digital ads, social pressure, and rapid product turnover make ultra-fast fashion irresistible, while habits and marketing intensity make breaking the cycle extremely difficult.

As a result, even in countries that traditionally value heritage and quality, consumers may feel conflicted about their choices.

Explosive Growth v/s Regulatory Lag

SHEIN knows how to scale. And fast. Localised website, French-language customer service, and EU logistics hubs (Belgium/Netherlands), leveraging TikTok and Instagram “micro-influencers”, flash sales and aggressive app engagement (push notifications, gamified coupons), attracting younger, digitally native audiences. Its textbook - and it works.

Regulations are often just playing catch-up to this explosive growth. Before the 2025 fine, SHEIN operated freely with cross-border VAT advantages and minimal customs scrutiny. That kept prices 30–40% below European fast fashion.

The French state has since tightened oversight, but enforcement lagged behind SHEIN’s explosive growth.

Subject Matter Opinion:

While SHEIN has a strong revenue generation in France, its launch in Paris and, especially, in the BHV can only be deemed as a misassessment. They might have had their rationale and hypotheses on entering the French market, but the current reputational and regulatory challenges are going to be hard to overcome. France is further pushing new laws on fast fashion (taxes, ad bans, environmental transparency), SHEIN will have to work on its ESG (environmental/social governance) credentials: e.g., supply chain transparency, recycling initiatives, sustainable materials, fair labour claims. If they don’t, they risk stricter regulation or brand‑damage and eventually revenue. Despite all this, SHEIN’s online channel continues to thrive. The government’s threat to ban the site, which has already been sanctioned several times, is widely seen as unrealistic. Industry leaders also lament that the anti-fast-fashion bill has yet to be passed. (ref: Le Monde)

(Re)Create a Sustainable Economy: Macromarketing Issues, Waste, and With regard more specifically to waste management” by Valérie Guillard and Dominique Roux — published in the Journal of Macromarketing.